A quick quiz.

Which famous battle was fought on October 21st 1805?

…

…

A gold star and a tick in your British values impact box if you correctly answered ‘The Battle of Trafalgar’.

The scenario was this: Admiral Nelson (one arm, one eye. 5 and a half feet ‘tall’) commanded his ship, HMS Victory. Looking across (with his one eye) he would have seen Napoleon’s Franco-Spanish fleet arranged before him. Their aim – to defeat the English fleet in a decisive battle, making way for an invasion of Britain. If Nelson’s force fell, the country would fall.

Nelson had twenty seven ships. His enemy had thirty three. And Nelson had a plan…

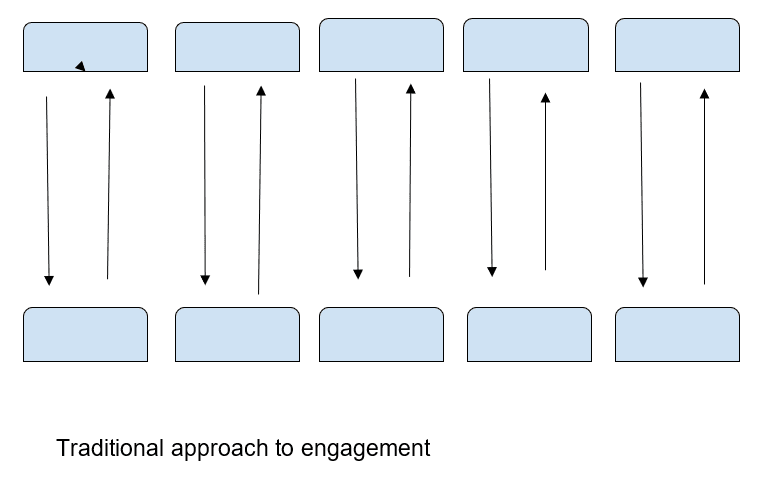

In traditional combat, both sides lined up parallel to each other and fired until one side – weakened by overwhelming firepower, loss of men, ships, etc – would surrender. This meant arranging cannons along the length of the ships. Commanders positioned themselves in the middle to control the battle. It meant centralised control, issuing orders by way of flags to direct operations.

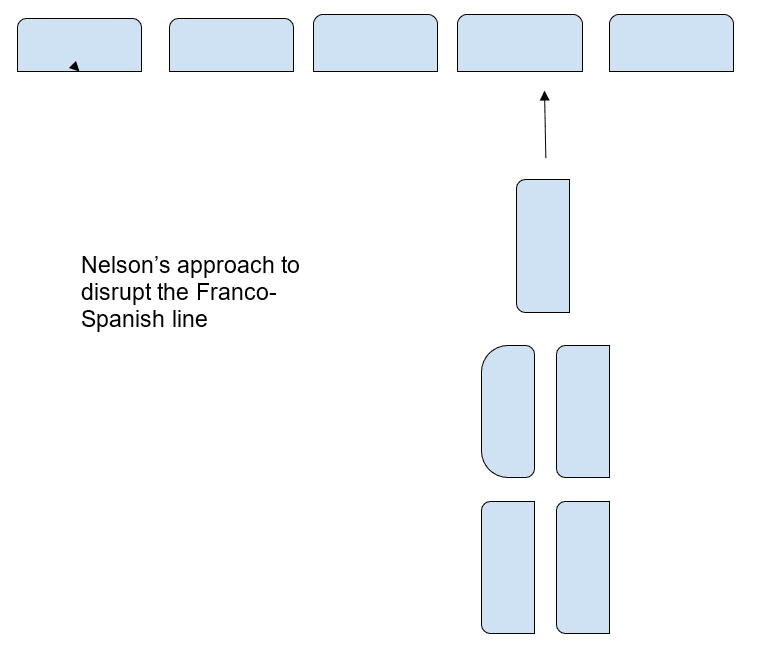

What Nelson planned was a different approach. He set his fleet off towards the Franco-Spanish line with two columns at a perpendicular angle, breaking the line into three parts. His idea was to catch the enemy off guard, scatter the ships and create chaos so that the enemy’s chain of command could no longer function:

This, on paper, looks relatively easy as a manoeuvre. In reality, it meant sailing ships with up to 850 sailors, positioning the vast amounts of canvas, 26 miles of rope and 37 separate sails across stormy seas whilst all the time loading, aiming and firing cannons. Cannons were stationary and couldn’t be moved to fire ‘forward’. Nelson’s ships would be effectively defenceless as they approached the enemy. However, once they had broken through, they could fire at point blank range and cause much more damage than in the normal way.

What was – and remains – interesting about the battle is how Nelson approached and led the captains of his ships. They were to act on their own initiative once they had broken through the line. He allowed – indeed he expected – them to use their own initiative. This was a culture he had cultivated over time with his own forces. At the heart of his leadership style, Nelson had created an environment that rewarded and encouraged individuality, creativity, adaptability and innovation. His opponents relied on commands coming down through a centralised chain and following them to the best of their ability. The British fleet had what has been described as a ‘cultural advantage’ rather than a technical one. One where they were trusted to act with their own skills and experiences.

The result? Nineteen of the Franco-Spanish fleet were captured. Nelson didn’t lose a single ship.

The above is taken from General Stanley McChrystal’s excellent book ‘Team of Teams’.

Trafalgar was won not because the British fleet was 5 or 10% more ‘effective’ or ‘efficient’. It won because it was culturally able to innovate and to adapt to new circumstances. Commanders had the skill, the will, the agility and the permission to adapt to new circumstances.

It serves as a metaphor for the importance of trust, autonomy and accountability that lies at the heart of what it means to be a leader within Wellspring.

I would argue that securing operational excellence and school improvement is only the start of the journey – not the destination.

School leaders too often make decisions based on ‘that’s what Ofsted/the LA/the Trust etc want’. How about doing things based on what children need instead? What if you were encouraged as a leader to take decisions, be accountable for them, be allowed to succeed and fail, learn and move on? That’s what it means to be a leader in Wellspring.

Rather than parroting the current, soon to be forgotten, mantra of ‘intent, implementation, impact’, what if we, as leaders and experts, design curriculums around entitlement? Entitlement of excellence and opportunity that changes the narrative and uses a different vocabulary.

How can we, as leaders, improve the future prospects of our young people, their families and their communities in a world transforming around us with Artificial Intelligence, climate change, algorithmic control of our decisions and a weakened political discourse?

We teach children to read, write and add up to the highest standard. That is a given. But let’s do so in ways that produce ‘bright, shining eyes’ – that gives them confidence, life skills, opportunities for self expression and regulation. That teaches them to think critically and accept/embrace difference. That teaches them social responsibility and makes them contributing members of society and enables them to appreciate art and beauty and wonder. That teaches them the date of the Battle of Trafalgar, but sets it into the wider historical, military, social and economic context of the conflict.

That makes learning memorable. That creates schools where everyone – young and young at heart – bloom and flourish. Where magic occurs.

This is our challenge – not to wait for the central command to issue their orders, their framework, their subject specifications, their workbooks, their definition of success and failure. But to charge straight at the prevailing orthodoxy with our skills, experience and courage. Wellspring is cultivating a unique environment – giving leaders at all levels the space to author their own vision based on what our young people, families and the community need – not what others dictate they want.

A battle worth fighting?